Thursday, May 25, 2006

Flying Machine

Da Vinci's sketches find new life.

By Jack Penland

May 16, 2006

For thousands of years, man dreamt of flying, and one of the biggest dreamers was Leonardo da Vinci. Five hundred years ago he studied and dissected birds, trying to find the secret of flight. He made notes, and initial drawings, but that is as far as he went.

Two Seattle area men chose to finish the job, building a full size flying machine with flapping wings. Today such things are called ornithopters. While others before had created models based upon the drawings, retired engineer Sandy McLaughlin and retired schoolteacher John Grove wanted to add the detail that da Vinci might have done. McLaughlin explained he wanted, "to try and do what he (da Vinci) could have done if he kept working on aviation."

Read more here

By Jack Penland

May 16, 2006

For thousands of years, man dreamt of flying, and one of the biggest dreamers was Leonardo da Vinci. Five hundred years ago he studied and dissected birds, trying to find the secret of flight. He made notes, and initial drawings, but that is as far as he went.

Two Seattle area men chose to finish the job, building a full size flying machine with flapping wings. Today such things are called ornithopters. While others before had created models based upon the drawings, retired engineer Sandy McLaughlin and retired schoolteacher John Grove wanted to add the detail that da Vinci might have done. McLaughlin explained he wanted, "to try and do what he (da Vinci) could have done if he kept working on aviation."

Read more here

The Physics of . . . Waterslides

Hurtling Toward Chaos

When waterslides reach a certain speed, no scientist can predict their behavior

By Elizabeth Svoboda

DISCOVER Vol. 26 No. 07 | July 2005 | Astronomy & Physics

Standing 76 feet above Orlando, Florida, staring down the throat of the Blue Niagara slide at the Wet’nWild water park, some riders have been known to have second thoughts. Powerful pumps churn the cascading water at the top of the slide into a furious froth, muffling the sound of parkgoers seven stories below. “Just go for it!” the ride operator urges, and another human torpedo surrenders to the froth, accelerating to a velocity of about 40 feet per second while careering through the slide’s 300 feet of looping tubes.

“Yup, that’s a crazy one,” engineer Marvin Hlynka says, chuckling. Hlynka works for WhiteWater West Industries, a firm in Richmond, British Columbia, that designed the Blue Niagara and other extreme waterslides. It’s his job to use science to find new ways to scare riders out of their minds, but there’s a limit to how much his equations and computer programs can help him. In the alternate universe of waterslide design, Newtonian models don’t always work, and chaos lurks in every hairpin turn. “In terms of actually predicting where a particular drop of water or a particular body is going to be in the slide at any given time, you can’t do it,” Hlynka says. “It’s just not possible.”

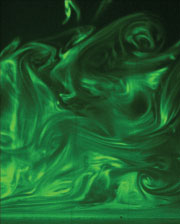

Photo Courtesy of V.S.R. Somandepalli, Y.X. Hou and M.G. Mungal, Stanford University

SMOKE IN THE WATER

The swirling eddies in a turbulent stream—shown here in a laboratory simulation at Stanford University—follow the same chaotic physics as does the smoke rising from a cigarette. The water is flowing from left to right and has been dyed to better reveal its patterns.

Read full story

When waterslides reach a certain speed, no scientist can predict their behavior

By Elizabeth Svoboda

DISCOVER Vol. 26 No. 07 | July 2005 | Astronomy & Physics

Standing 76 feet above Orlando, Florida, staring down the throat of the Blue Niagara slide at the Wet’nWild water park, some riders have been known to have second thoughts. Powerful pumps churn the cascading water at the top of the slide into a furious froth, muffling the sound of parkgoers seven stories below. “Just go for it!” the ride operator urges, and another human torpedo surrenders to the froth, accelerating to a velocity of about 40 feet per second while careering through the slide’s 300 feet of looping tubes.

“Yup, that’s a crazy one,” engineer Marvin Hlynka says, chuckling. Hlynka works for WhiteWater West Industries, a firm in Richmond, British Columbia, that designed the Blue Niagara and other extreme waterslides. It’s his job to use science to find new ways to scare riders out of their minds, but there’s a limit to how much his equations and computer programs can help him. In the alternate universe of waterslide design, Newtonian models don’t always work, and chaos lurks in every hairpin turn. “In terms of actually predicting where a particular drop of water or a particular body is going to be in the slide at any given time, you can’t do it,” Hlynka says. “It’s just not possible.”

Photo Courtesy of V.S.R. Somandepalli, Y.X. Hou and M.G. Mungal, Stanford University

SMOKE IN THE WATER

The swirling eddies in a turbulent stream—shown here in a laboratory simulation at Stanford University—follow the same chaotic physics as does the smoke rising from a cigarette. The water is flowing from left to right and has been dyed to better reveal its patterns.

Read full story